- About

- Programs

- Issues

- Academic Freedom

- Political Attacks on Higher Education

- Resources on Collective Bargaining

- Shared Governance

- Campus Protests

- Faculty Compensation

- Racial Justice

- Diversity in Higher Ed

- Financial Crisis

- Privatization and OPMs

- Contingent Faculty Positions

- Tenure

- Workplace Issues

- Gender and Sexuality in Higher Ed

- Targeted Harassment

- Intellectual Property & Copyright

- Civility

- The Family and Medical Leave Act

- Pregnancy in the Academy

- Publications

- Data

- News

- Membership

- Chapters

Universities in the West Bank and Gaza

An American professor revisits Palestine.

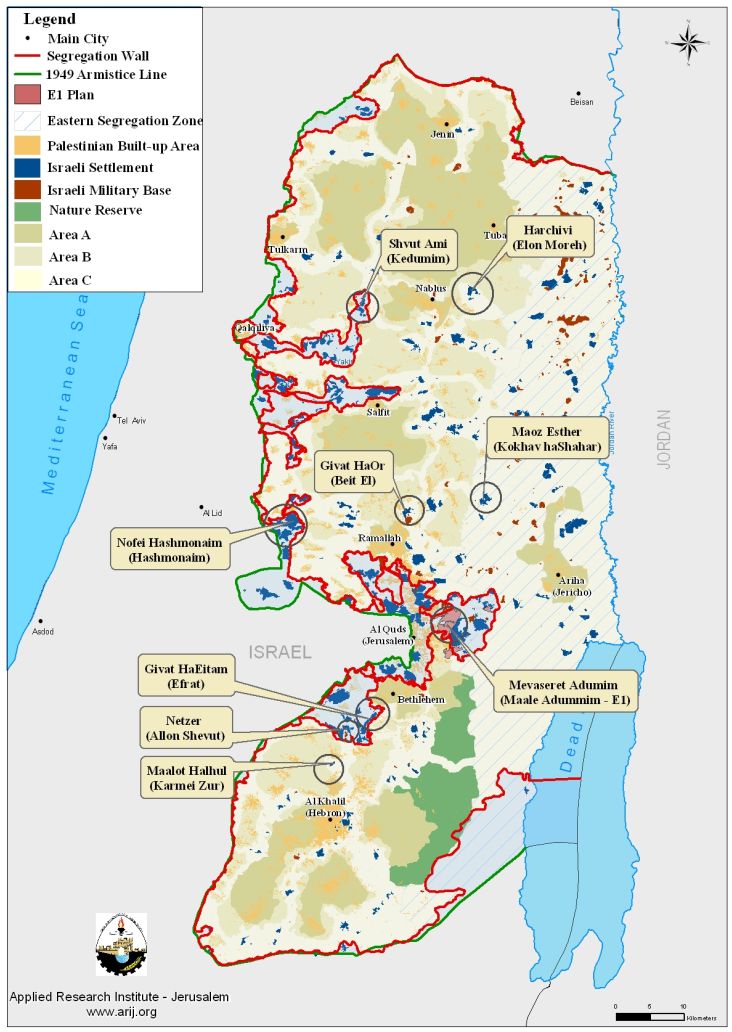

In 1990, I wrote in Academe about higher education in Palestine, in particular the difficulties of operating under military occupation. Then, in 2004, I updated the information, noting how much more difficult communication had become but mentioning some hopeful developments in teaching and research. I wish that I could now write a more optimistic piece. The West Bank and Gaza are still under varying degrees of occupation, as shown to some extent by the map below. Traveling even short distances can be a daily trauma for faculty members and students.

As a result of the difficult conditions, communication and cooperation among the West Bank and Gaza universities are minimal. Greatly expanded settlements in the Occupied Territories, illegal under international law, have taken over a substantial amount land and resources, particularly water, and related restrictions make travel within the West Bank and Gaza difficult. The wall that Israel built has cut off the West Bank from Israeli territory and in many cases has separated villages and kept farmers from their fields; the construction of the wall and additional security checkpoints has also made traveling within the Occupied Territories very difficult. For example, faculty members and students from Birzeit University just north of Jerusalem must travel many miles and pass through many checkpoints to get to Bethlehem University just south of the city should they wish to carry out collaborative work. Entry into Jerusalem is impossible for most West Bank academics; Gaza is even more isolated. I participated in a workshop in Ramallah on special education for which a few permits had been granted for attendees from Gaza, not all of whom were able to get there.

Day-to-day classes carry on, without the frequent shutdowns of the universities that characterized the intifada periods, but other impediments remain. The president of Birzeit University told me about how all of the donated lab equipment for an enhancement of their labs arrived, except for the crucial centerpiece, which was not allowed in. The Israeli military invaded Al Quds media center in Ramallah and confiscated its instructional equipment. Israel formally annexed the Hind Husseini College for Women, part of Al Quds University in East Jerusalem, making it subject to a different set of restrictions. The college has been unable to complete a renovation because it is not allowed to install an elevator in the four-story building, making access for the disabled impossible.

Islamic University of Gaza (2010)

Al Azhar University, Gaza, in a quiet period

Al Quds University, Abu Deis

Al Quds University, Abu Deis

An-Najah University, Nablus

Arab American University, Jenin

Several for-profit institutions, including the Arab American University of Jenin, which is organized along American lines, have been established recently. The two largest universities in the West Bank are An-Najah National University in Nablus, with twenty thousand students, and Al Quds in Abu Deis and Jerusalem, with fourteen thousand students on campus and seventy thousand taking part in its Open University. In addition to giving talks on statistics during my visit last spring, I was invited to address the Assembly of University Councils on the role of faculty senates in university governance. The uneasy combination of students, faculty members, administrators, trustees, and representatives of the Ministry of Higher Education produces many conflicts with which US academics are very familiar. Faculty members asked me how administrators can be made to follow through on policy agreements, and administrators asked how faculty can be motivated to engage in serious strategic planning that recognizes that resources are limited and priorities need to be established. Campus rivalries and difficulties in communication make it hard to engage in cooperative projects across disciplines within universities as well as among universities.

Birzeit University

Although religious issues appear not to be a significant factor, political parties and family allegiances certainly are. The scenes on campus are not unlike those in the United States. However, it is the case that although years ago almost no women at Birzeit covered their hair, now the uncovered female heads are rare among the student body (less so among the faculty) there and at other campuses.

Bethlehem University

Several of the universities have medical schools and most have law (an undergraduate degree as in Europe) and engineering schools. At Al Quds, the engineering dean is a woman and half of the students in engineering are female. Most of the faculty were trained in the United States or Europe. Women are scarce in the senior faculty ranks, in part because of a traditional reluctance of families to support study abroad by their daughters. An encouraging note is that of thirty-four Palestinian faculty members currently studying for PhDs in the United States under an Open Society–State Department program, eleven are women. Also encouraging, in my view, is that the universities are concentrating on undergraduate study and master’s programs geared to Palestinian needs; initiatives include environmental studies (including water resources), public health, and special education. As we know, PhD programs are very expensive and generally take a long time to become competitive, and in the past the Palestinian Authority has not paid enough attention to education that meet societal needs.

Many of the universities have extensive community-outreach programs. For example, in the Old City of Jerusalem, Al Quds has a Center for Jerusalem Studies and a Women’s Empowerment Center, whose mission is “Giving women the tools they need to live in dignity.” In addition to research and a master’s degree program, the Center for Jerusalem Studies, situated at the site of two Mamluk-era hamman (baths), has a program designed to introduce Palestinian heritage not only to visitors but also to locals and to children from the West Bank and Gaza (who are allowed to travel to Jerusalem up to age twelve).

Entrance to the Palestinian quarter in the old city of Jerusalem

Center for Jerusalem Studies in the Old City of Jerusalem

An enterprise of special interest to me was the Math Museum at Al Quds University. I particularly liked the model of the Königsberger bridge problem, although the director was quite disappointed to learn that I was very familiar with its solution (namely, that it is impossible for the good citizens of Königsberg to make a circuit of their seven bridges, crossing each only one time and returning to their starting point). An event that coincided with my campus visit was the museum’s contest to see who could memorize the most digits of pi.

Students at the Math Museum, Al Quds

Because they need more qualified faculty members in many disciplines, administrators, faculty, and students are eager to improve the chances of the best students getting support for doctoral study abroad. There are US-funded programs like the Open Society fellowships mentioned above and Fulbright grants as well as opportunities in Canada, Australia, and Europe, but these are highly competitive and limited in number. Many faculty members, even those educated in the United States, don’t understand the admissions and financial-support processes in this country. In particular, they are often unaware of the opportunities provided by teaching assistantships (including, at some institutions, assistantships with service in the Arabic department no matter what field the student is studying). Deadlines are a big issue—many times I have been asked during the summer about fall admissions. Another problem is the grading system in Palestinian universities, which do not share the grade inflation of American institutions. Grades higher than 90 are rare, and with many US universities converting number grades according to a scale where a 93 is an A, an 85 is a B, and so forth, the students have difficulty meeting minimum GPA requirements. Of course, English is a problem, but in my fairly extensive experience I have found that Palestinian students arrive with decent knowledge and quickly acquire very good language skills.

A few students and faculty members from the West Bank and Gaza are enrolled in advanced degree programs in Israeli institutions, but getting permission to study and then getting to campus once admitted are difficult. It should be said that in general the problems are mostly ones of access, and not of treatment by faculty and fellow students once there.

If I am to avoid painting another rather gloomy picture in another nine years, the Israeli government will need to facilitate access and transportation in the West Bank and to and from Gaza. Palestinian governmental and educational institutions must improve cooperation among themselves and convince local successful businesses to invest in education to serve the students, to continue to train and retain faculty members, and to provide the needed infrastructure. Palestine’s primary resource is its people, not oil or minerals, so funding is also needed from oil-rich states, Europe, and the United States. Ultimately, higher education in the West Bank and Gaza will not achieve excellence without the broader solution so desperately needed.

Mary W. Gray, professor of mathematics and statistics at American University, has visited the Palestinian universities for more than thirty years, lecturing and collaborating with faculty members there on education and the conduct of surveys. She chairs the board of directors of a nongovernmental organization with offices throughout the Middle East and North Africa. Her e-mail address is [email protected].