- About

- Programs

- Issues

- Academic Freedom

- Political Attacks on Higher Education

- Resources on Collective Bargaining

- Shared Governance

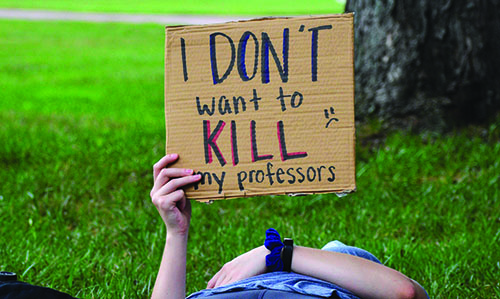

- Campus Protests

- Faculty Compensation

- Racial Justice

- Diversity in Higher Ed

- Financial Crisis

- Privatization and OPMs

- Contingent Faculty Positions

- Tenure

- Workplace Issues

- Gender and Sexuality in Higher Ed

- Targeted Harassment

- Intellectual Property & Copyright

- Civility

- The Family and Medical Leave Act

- Pregnancy in the Academy

- Publications

- Data

- News

- Membership

- Chapters

The Necroliberal University

COVID-19, racial violence, and the management of death.

A friend recently related how, in a meeting to discuss the reopening of their public college for in-person instruction in the fall, their dean’s comment that, “yes, some of the returning students will get sick, and . . .” mysteriously trailed off, allowing this professor to wonder what words were to come next. And die? And some faculty and staff, too? Both? This frank admission, followed by an even franker vagueness, seems the university line these days among those campuses holding classes and opening dorms during a pandemic. Yes, some students and staff will get sick and die. And no, we don’t know how many, and, yes, that’s okay, too.

In the same week that Indiana University’s president announced his plans to reopen in the fall, he sent an email expressing his “sadness and great concern” over the killing of George Floyd. The two statements, one full of managerial exuberance and technological jargon about “artificial intelligence” and “CLIA-certified laboratories” that will presumably keep us all safe and the other promising students of color a “campus environment where they feel safe, supported, and respected,” strangely echoed. Even as “some students will get sick” and other students of color face violence, in the minds of administrators the university is a site of safety and managerial order.

A pair of op-eds written recently by the presidents of two prominent midwestern campuses exemplified this projection of managerial capacity during crisis. Mitch Daniels, former Indiana governor and current president of Purdue University, in a public letter to all faculty and staff, wrote that Purdue “intends to accept students on campus in typical numbers this fall” and will “manage them aggressively and creatively.” The management that Daniels advocates involves a kind of fictive caesura among student, community, and faculty populations: “At least 80% of our population is made up of young people,” Daniels states. “All data to date tell us that the COVID-19 virus . . . poses close to zero lethal threat to them.” And while “the virus has proven to be a serious danger to other, older demographic groups,” he assures us that “we will keep these groups separate.” University of Notre Dame president John Jenkins, writing in the New York Times, took this management of risk a step further and said that the campus should be “willing to take on ourselves or impose on others risks—even lethal risks—for the good of society.” These risks, of course, are to be managed and mitigated as best they can.

Michel Foucault, in his famous coining of the term biopolitical, described how states arose to govern populations during times of the plague. Foucault argued that the power states are granted to separate people into categories such as citizen and alien, criminal and taxpayer, worker and disabled, and white and Black arose from the fundamental powers to divide populations during quarantine. And on some level, Daniels and Jenkins conjure this kind of population management, with their reassurance that they will “institute extensive protocols for testing; contact tracing and quarantining; and preventive measures, such as hand-washing, physical distancing and, in certain settings, the wearing of masks.” The piling of Latinate words and pop-scientific jargon suggests that the campus pandemic has a soothing, orderly texture, as though the virus will be sorted according to the Dewey decimal system or perhaps screened like luggage by the Transportation Security Administration. Until, of course, one realizes the opposite—the panopticon these administrators construct through language is not, as with the quarantine, designed to preserve life, however brutally, but rather to invite and then contain death.

Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbembe revises Foucault’s neologism in his groundbreaking work Necropolitics by positing that the other side of the management of living is the management of dying. In the colonial context, the management of death can appear as refugee camps or extractive and toxic industries such as oil production in the Niger Delta; it can look like death squads, massacres, and gang wars. In the first world, it appears more subtly as lower life expectancies for African Americans and the poor, as the mass detention of migrants, as a thousand or more killings by police each year. Thus, what is shocking about the Daniels and Jenkins statements is not only that they argue for opening their campuses during a pandemic but that they openly accept death as something to be managed, controlled, and even invited. Because this is happening in the context of immense wealth and privilege—Notre Dame, with its $10 billion endowment, is one of the wealthiest universities in the world—this necropolitical turn might be better captured by another term: necroliberalism.

The liberalism of the university in both presidents’ messages requires elaboration. University administrations do not dismiss mask-wearing or claim there is no virus or concoct conspiracy theories that the coronavirus was engineered in a laboratory in China. The Indiana University reopening plan—a glossy thirty-page brochure—includes spacing charts, classifications of masks, a multiethnic cast of models at computers holding vials of blood, instructions for washing hands, contingency plans such as quarantine dormitories, provisions for virtual medics, and details about ventilation; it presents a world of measurement, technology, liberalism, and scientific administration. And yet nowhere does one find a description of what actually happens when someone is seriously infected with COVID-19, the lungs filling with fluid, the organs failing, the spiking fevers, the spread of strange rashes, the loss of taste and smell, the permanent lung damage, the hallucinations from fever, the disorientation, the fear, the death. The university administration knows very well that its own plan is impossible to implement safely: students and staff are to “self-report” when they feel ill; people are to return to work after ten days, when we know that presymptomatic people are the most likely to spread the disease. Indeed, the New York Times reported that, as of mid-September, more than 88,000 college and university faculty, staff, and students had contracted COVID-19 since the pandemic began, and sixty had died.

As scholars Jason England and Richard Purcell recently pointed out in an op-ed in the Chronicle of Higher Education, the statements from university administrations on the murder of George Floyd carry with them a similar passive voice. They mention “systemic racism,” they express regret, and they embrace a diverse university, but nowhere do they condemn the police as a racist institution or acknowledge that university police forces are themselves complicit in racial violence. Indiana University president Michael McRobbie’s statement, like many others, refers to the killing of Floyd as “senseless” but quickly pivots away from suggestions for structural change or condemnation of anything broader than “hate and intolerance.” McRobbie’s statement is even stranger for the suggestion that “black and brown individuals” have been “subjected to disturbing violence in recent years,” linking the death of Floyd with the rise of “hate groups”—not the longer history of slavery, Jim Crow, lynching, or mass incarceration.

This parallel vision of necroliberal management was made clear in Purdue University’s response to the Black Lives Matter movement: it promised to form a task force modeled on the Safe Campus Committee that the university has formed to study COVID-19. At no time did the Safe Campus Committee itself take up the problem of the unequal medical impact of reopening on different racial communities, with African Americans likely to be particularly hard hit by the virus. Nor did Purdue move to study racism on campus several years ago, when on at least five different occasions white supremacist fliers appeared on the campus, and on one occasion anonymous students arranged desks in a campus building in the shape of a swastika. And Purdue’s administration was silent when protesters, including African American Purdue students, were teargassed by local police following the largest protest in the area since 1969 in response to the murder of George Floyd.

Another way to read managerial necropolitics in higher education is to foreground racism as what scholar Ruthie Gilmore calls “the state-sanctioned or extralegal production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death.” These deaths may be both personal and institutional. Numerous reports have underscored the special vulnerability of historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) during the pandemic. Vast numbers of HBCU students are on Pell Grants or come from low-income communities. They arrive at college having “dodged the bullets” of police violence only to come face to face with another public health crisis at their university, one that some HBCUs may not survive because of their own precarious financial status—underfunded, underresourced, and lacking the large endowments of either elite white-majority campuses or large public universities. Universities, in other words, reproduce, or rather distill and manage, the death-making practices that occur outside their walls.

As English and Africana studies professor Jodi Melamed reminds us, liberal multiculturalism emerged in the postwar years as a project of race management, explicitly opposed to movements for Black liberation or revolutionary socialism. By advancing policies of desegregation and multiculturalism and promoting a Black and brown professional-managerial class, liberal antiracism became the official language of the US imperial state. The university has had a key role in producing antiracist liberalism as a normative mode of power and the means by which US liberal democracy could be spread abroad. The university, according to Melamed, was structured to produce “reasonable, law-abiding, and good global citizens” who could manage the personnel and capital of transnational corporations—the biopolitical production of multicultural “human capital.” At the very moment when the contradictions of that project exploded into public view with the rise of the third world studies movement and a wave of Black power and antiwar student strikes, the project of liberal antiracism again reshaped itself from one of desegregation and antiracism to one of diversity and individual identity.

Of course, the biopolitical management of liberal antiracism also quietly implies its other, the necropolitical liberal management of racial violence. If the university is a space in which diversity is to be managed, the violence of racism is not challenged so much as elided, moved aside, and kept away from campus as practice but also as discourse. In his famous concurring opinion in Bakke vs. Regents, Justice Lewis F. Powell defined the role of affirmative action as a matter less of racial justice than of optimal academic outcomes: a diverse student body is necessary to equip future managers at J. P. Morgan Chase to manage a global investment portfolio. The quotas he opposed, by contrast, would have moved toward actual racial redistribution. Race became a question of personal and individual rights rather than of group rights. The university thus became a place where, it was imagined, individuals would be stripped of their past, their context, and their communities rather than a place where complex social questions exist and are negotiated. “Educational pluralism,” in Powell’s turn of phrase, is a managerial fiction that covers over the white supremacy of the labor market, police force, and prisons.

The cry to defund and abolish the police is also closely related to a vision of higher education that universities themselves have violently opposed. The roots of movements for prison abolition lie in demands to redirect resources to spheres—like education—where public health is constructed with books rather than bullets. Free public education, free higher education, have been and ought to be central demands of movements to abolish the police. Yet universities, like good neoliberal subjects, have seen the public health crisis for higher education only as a reason for more privatization, more austerity. Rather than call for free education, administrators scramble to find get-rich schemes to close budget gaps—focusing one year on recruiting international students who paid, prior to the pandemic, exorbitant prices, and another on contracting with private vendors.

One can see the contradictions of necroliberalism in the privatized university. Purdue University recently signed a contract with food company Aramark to manage its dining operations in the student union. Aramark is notorious for being the food provider for dozens of private and public prisons. In 2018, students at New York University held a huge protest after Aramark served a “Black History Month” meal that included collard greens, watermelon-flavored drink, and Kool Aid. Protesters against Aramark pointed out that NYU was working with a company tied to the prison-industrial complex while serving up racist stereotypes to students already doubly vulnerable to the effects of mass incarceration. Contracting with Aramark at the height of a pandemic and mass protests against police violence returns us to the university as a staging ground of necroliberalism, the dividing line between the university and the carceral state becoming even thinner.

By pointing out the material investments of necroliberal university administrators, we disagree slightly with England and Purcell. While we would like university administrators to offer better statements, we don’t believe they are insincere. They express their condolences and their concern in a passive voice, free of conflict, because that is the frame through which they understand the university. And one should not view the statements as anything other than an administration of the uprising, a statement that acknowledges and attempts to reinforce the university’s role in producing “educational pluralism” as a normative mode of power. There may be death out there, but the university, in all its administrative passivity, has no role in it for good or for bad, as all the forces that produce such death, they imagine, stop at the limestone walls. One recent story in the New York Times expressed shock that some students went home during a pandemic to leafy upper-middle-class neighborhoods in Westchester County while others went to a trailer park—as if such class contradictions could not be possible. Isn’t the whole point of Haverford that the students are diverse but also fundamentally homogenized by their experience there?

As evidenced by the commitment to contracting with prison suppliers, Daniels’s necroliberal assignment of bodies into different categories—those who can get sick and those who cannot, the young and the old, those who are necessary for the university to continue and those who are expendable—is simply the conclusion of this logic. The university administration, so accustomed to keeping the violence of capitalism separate from its passive reproduction, cannot conceive of a pandemic in which such separations are increasingly difficult to maintain. Reading Daniels’s or McRobbie’s or any university administration’s plans on COVID-19, one realizes that they bear no resemblance to reality, no acknowledgment of how the virus spreads or of the people who are more likely to become seriously ill and die if they are exposed to it. Universities will “administer” this virus, with all its deadly impact and racial disparity, just as they manage racial violence through a language of administered diversity. That such necroliberalism, such polite administration of death, does not work and is not designed to work is beside the point. Like Theodor Adorno’s critique of instrumental reason, the “obdurate adherence to laws” is itself a kind of emptying out of the self into a logical apparatus that appears rational until one steps back and sees the madness of the entire system.

The chickens have finally come home to roost: the madness of liberal administration that once kept students separate from their communities, separate from the death outside, has become the logic of liberal administration. As of mid-September, the number of people who have fallen ill on campus since the pandemic started is roughly equivalent to the population of two large state universities, or five midsize universities, or thirty small liberal arts colleges. And predictably, the dead are mostly hourly employees: the silent, nameless victims of the illness whose lives have been made expendable in the drive to reopen. These lost workers are the tragic faces of the necroliberal university. It would be madness to reopen, but it was always madness. As James Baldwin remarked, we have “always been at the mercy of an ignorance that is merely phenomenal, but sacred . . . the better to be used by a carnivorous economy that slaughters and victimizes.” For many years the university has been imagined as a site removed, a place in which class, race, and social conflict can be managed. That era is over: the madness now has a glossy thirty-page brochure and an ever-increasing death count.

Benjamin Balthaser is associate professor of multiethnic literature at Indiana University South Bend. He is the author, most recently, of Anti-imperialist Modernism: Race and Transnational Radical Culture from the Great Depression to the Cold War, and he is the secretary-treasurer of his campus AAUP chapter. Bill V. Mullen is professor of English and American studies at Purdue University. His books include James Baldwin: Living in Fire, Un-American: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Century of World Revolution, and Afro-Orientalism.